Understanding Its Definition, Application, and Significance

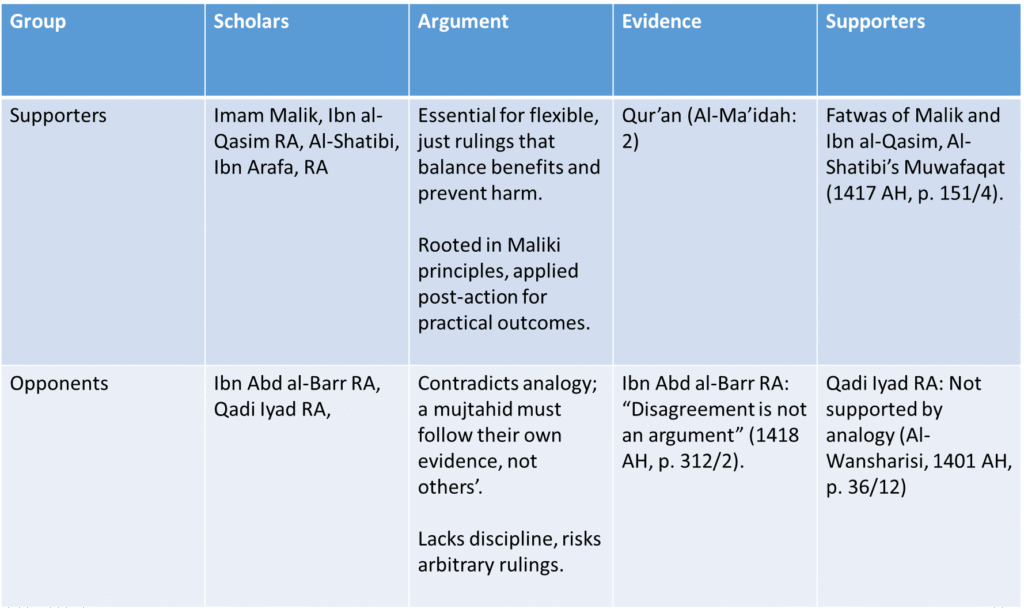

Definition of Taking into Account Disagreement:

Linguistic Definition: From Arabic “ra’i” (to observe/consider) and “khilaf” (disagreement), meaning to notice and weigh opposing scholarly opinions.

Technical Definition: A mujtahid reconsiders a ruling post-action, factoring in the opponent’s evidence to address consequences and achieve Shari’ah objectives .

Maliki emphasis: Applied before and after an event, especially post-occurrence, to mitigate harm.

1. Intellectual Richness due to disagreement and Legal Flexibility

Diverse Interpretations: Differences arise from varying interpretations of Quranic texts (e.g., ambiguous vs. clear verses) and Hadiths (varying authenticity and contextual understanding). This diversity enriches Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh).

Methodological Pluralism: Scholars from different schools (madhhabs) employ distinct methodologies (usul al-fiqh), such as qiyas (analogy), istihsan (juristic preference), or maslaha (public interest), leading to contextual rulings suited to different times and regions.

2. Adaptability to Context

Cultural and Regional Relevance: Early schools like Maliki (Medina) and Hanafi (Iraq) incorporated local customs (urf), ensuring Islamic law remained practical and adaptable. This flexibility addresses evolving societal needs, including modern issues unaddressed in early Islam.

3. Encouragement of Ijtihad

Scholarly Effort: Disagreements reflect the active engagement of scholars in ijtihad (independent reasoning), a process valued in Islam. This fosters continuous dialogue and prevents stagnation, allowing the tradition to respond to new challenges.

4. Pluralism Within Unity

Respect for Valid Differences: Ikhtilaf is recognized as legitimate when grounded in sound principles. This pluralism prevents rigid uniformity, acknowledging multiple valid approaches while maintaining core beliefs (aqeedah) and practices.

5. Consensus (Ijma) and Boundaries

Balancing Diversity and Unity: While consensus is binding, disagreement is tolerated within scholarly boundaries. This balance ensures stability without suppressing diversity, as seen in the coexistence of four Sunni madhhabs.

6. Preventing Sectarianism

Ethical Guidelines: Respectful disagreement is emphasized to avoid division. Scholars historically upheld adab al-ikhtilaf (etiquette of disagreement), promoting mutual respect and minimizing conflict.

7. Theological and Historical Development

Shaping Islamic Thought: Theological debates (e.g., Ash’ari vs. Mu’tazili on free will) and legal disagreements have driven intellectual progress, contributing to Islam’s rich theological and juristic heritage.

8. Guidance for Laypersons

Taqlid (Following a School): Lay Muslims follow a madhhab, reducing confusion while benefiting from scholarly diversity. This system ensures religious practice remains accessible and orderly.

Challenges and Considerations:

Potential for Division: Unmanaged disagreements can fuel sectarianism, emphasizing the need for adherence to ethical discourse.

Balance with Consensus: While diversity is valued, consensus on fundamentals (e.g., pillars of Islam) maintains communal cohesion.

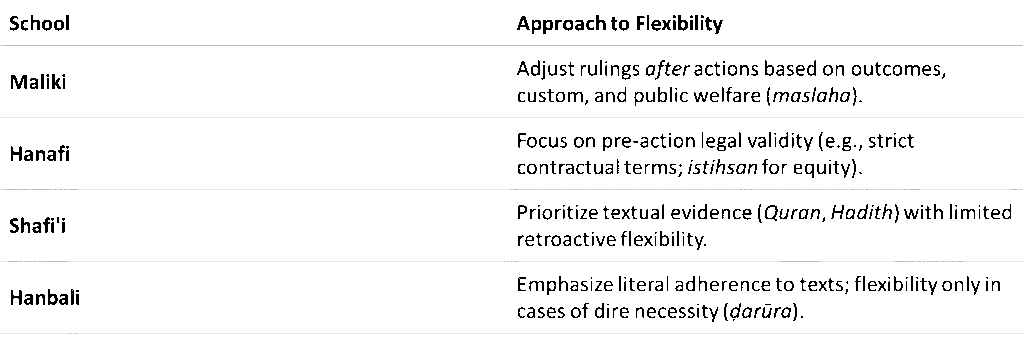

Disagreement (ikhtilaf) in the Maliki school uniquely emphasizes “post-action flexibility“, a distinctive feature of Maliki jurisprudence (fiqh). This principle prioritizes practical outcomes, societal welfare, and adaptability after an action has occurred, allowing rulings to be adjusted based on real-world consequences or contextual needs.

1. Core Maliki Principles Enabling Post-Action Flexibility

a) الاعمل بِعَوَاقِبِ الأُمُور(Considering Consequences)

Maliki jurists emphasize evaluating the results of an action or ruling, even if it initially appears valid. If implementing a strict ruling leads to harm (ḍarar) or hardship (mashaqqa), they may revise it to align with broader Islamic objectives (maqāṣid al-sharīʿah), such as justice or public welfare (maslaha).

Example:

If a contract is technically valid but leads to exploitation, a Maliki judge might annul it to prevent injustice, even if other schools uphold its formal legality.

b) العُرْف (Custom andعَمَل أَهْل المَدِينَة Practice of Medina:

The Maliki school heavily incorporates local customs (urf) and the lived practices of Medina’s early Muslim community. This allows rulings to adapt to societal norms and post-action realities.

Example:

In financial transactions, Malikis might validate unconventional agreements if they align with local customs, even if they deviate from strict contractual formalities.

c) سَدُّ الذَّرَائِعBlocking the Means

While Malikis use this principle to prevent harmful actions, they also apply it retroactively. If an action (even a permissible one) leads to harm, they may restrict it after the fact to protect societal interests.

Example:

If a permissible business deal inadvertently enables usury (riba), Malikis may nullify it post-transaction to “block the means” to harm.

Comparison with Avoiding Disagreement:

Taking into Account Disagreement:

Maliki-specific: Reconsiders rulings post-action, using opponent’s evidence to address consequences.

Mandatory in some cases, used in transactions (e.g sales).

Avoiding Disagreement:

General principle: Choose the safer opinion when evidence is equal, often in worship.

Recommended, not mandatory, based on piety and precaution.

“O you who have believed, do not violate the rites of Allah or [the sanctity of] the sacred month or [neglect the marking of] the sacrificial animals and garlanding [them] or [violate the safety of] those coming to the Sacred House seeking bounty from their Lord and [His] approval. But when you come out of ihram, then [you may] hunt. And do not let the hatred of a people for having obstructed you from al-Masjid al-Haram lead you to transgress. And cooperate in righteousness and piety, but do not cooperate in sin and aggression. And fear Allah ; indeed, Allah is severe in penalty.”

(Surah Maida 5:2)

The Maliki school places immense weight on preventing harm (darar), injustice (zulm), and sin. If adhering strictly to an initial ruling (hukm) – even if technically valid based on one interpretation – leads to an outcome that constitutes ithm (sin, like upholding an injustice) or ‘udwan (aggression/transgression, like causing undue hardship or violating a higher principle of justice), cooperation with that outcome becomes forbidden by this verse.

This warns against letting personal feelings (like animosity towards a litigant) or external pressures cloud judgment and lead to an unjust ruling or the rigid upholding of a ruling that causes aggression (‘udwan). Justice must be impartial.

Download This article in PDF or PowerPoint